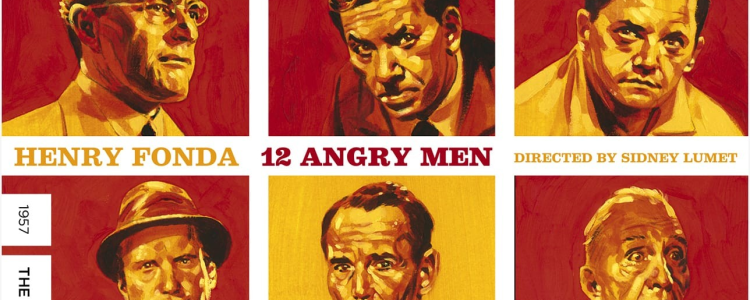

12 Angry Men: The Dangers of Preconception and Prejudice Pose for Justice and an Assured, Taut Example of Minimalist Filmmaking

Written by Matei, BSB Reporter

It is safe to assume that a majority of people avoid watching old movies in favour of the new. commercial, contemporary film: topped with today’s popular stars, spectacular cinematography and unimaginable visual effects. They have been dominating cinemasfor the past decade and the never-ending slew of unoriginality – in the form of sequels, prequels, remakes and franchises – pile on top of the films that have created the technical and creative foundation onto which they all stand. The foundation of character, theme, message, tension, style and dialogue.

One of the last century’s most lucrative film directors, Sidney Lumet, debuted with 1957’s courtroom drama 12 Angry Men, with a budget just over a mere $300,000 and a range of mid-tier Hollywood actors,black and white film,a small crew andone location. Nowadays, 12 Angry Men is now regarded as ‘a textbook for directors interested in how lens choices affect mood’ (Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert)and‘a masterclass in the pure dynamism of acting’ (Empire, William Thomas).

The plot is simple. After hearing the defence and prosecution cases regarding a young Spanish-American killing his father, the jury is sent into the jury room in order to reach a complete verdict. When one of the jurors stands up and identifies ‘reasonable doubt’ in the prosecutor’s case, what ensues is a verbal and psychological battle between the men, held only to believe the accused is guilty by prejudice, peer pressure and an unwillingness to question evidence.

Rarely do movies have ‘debate’ as their main focus, which is what makes Lumet’s debut effort such a standout. It enthrals, captivates and encourages critical consideration – all through argument and speech, with a deliberate lack of visual spectacle or action. With this, the dialogue inherently becomes the action, with every argument becoming a fist fight amongst the characters. The film works thematically, dramatically and technically in order to create a reflection of America’s abused civic duties and democracy.

Lumet, and screenwriter Reginald Rose, heavily tackle themes such as prejudice, racial injustice and bias in the judicial system. The jurors are purposefully left nameless, perhaps as a message to the audience: character isn’t the point. The ongoing argument is, with each juror representing different societal archetypes, the whole group then represents American democracy. From the very first voting call within the group, Lumet suggests the presence of moral corruption within the established ‘democracy’ – “It’s an open and shut case”, says one of the jurors without any consideration and discussion, in an effort to challenge the sole juror who pleaded ‘not guilty’. Following the questioning of evidence, the encouragement to think critically and the act of identifying ‘reasonable doubt’ within the prosecutor’s case – acts which only the sole juror sustains – prejudices and preconceptions among the other jurors are gradually revealed.

Lumet asks, can we truly trust the judicial system when the final verdict is influenced by racist inclinations, personal matters and an overall apathetic attitude towards the case? Is it true justice?

Empowering these themes and questions is Lumet’s masterful direction. Along with cinematographer Boris Kaufman, Lumet develops a self-titled ‘lens plot’ technical strategy for the duration of the film; as he explains in his autobiography, a ‘lens plot’ is essentially the use of camera angles, settings and lenses to technically cooperate with – or even create – tone and emotion. This is exemplified by camera angle character motifs to represent their views (seen with the oldest juror, as his close-ups fill the frame to empower his to-the-point lines) or rather Lumet’s choice to increase the focal lengths of his lenses as the plot progresses and the tension grows. This creates the visual effect that the room is decreasing in size, as the background appears closer to the characters; a nifty visual trick which greatly services the dramatic aspect of the film.

The film opens with a wide angled, upward tilt showing the entrance of the courtroom from the exterior, focusing on the four large pillars that hold the roof of the building, onto which ‘justice’ is written: perhaps, a metaphor for the jurors, as ‘justice’ relies on their ‘fair’ verdict – just as the courtroom relies upon those pillars to hold it.

As eleven of the jurors put their hands up in favour of a ‘guilty’ verdict, they themselves have become visibly associated with ‘guilty’. Rather, they themselves are ‘guilty’ of judicial misconduct – Lumet highlights, visually and thematically, how moral corruption is the reason for injustice in America’s flawed democracy. ‘Reasonable doubt’ is a bare element of the American Constitution: a defendant is innocent until proven guilty – a prospect ironically neglected by the majority of the jurors who themselves, as established earlier, represent American society. Lumet’s message is troubling, yet by having one juror stand up against the injustice perpetrated in the jury room, the message becomes hopeful.

It is important to visit classics, such as this, in order to appreciate the progression of how film has evolved but also as a method to culture oneself about our past – with regard to society and the practicality of filmmaking. 12 Angry Men promises to engage and works as a great start in the exploration of the Golden Era of Cinema.

Please note that the British School of Bucharest is not responsible for the content on external pages and, as usual, we advise you to monitor your children’s online activity.